- Home

- Charlotte Gullick

By Way of Water Page 2

By Way of Water Read online

Page 2

Five minutes passed, and then the door opened and Jake walked back, his steps fast. Dale inhaled sharply, and Justy pretended he carried a half-gallon of ice cream instead of the stupid can. He set it in the new snow on the hood and pulled out a penny. Dale pushed Justy off her lap and got out to stand next to him. She didn’t step too close, unsure yet where the anger was settling in his body.

“Sullivan said he’d rather throw pennies in the street for kids than take money from an Indian.”

Jake cocked his arm and flung the penny at the storefront. It hit a window with a zing. Flakes landed on Jake’s red-and-black-checkered wool shirt, on Dale’s thin blue windbreaker and on their hair, making them seem like angels or ghosts. Justy looked to see if Sullivan was watching, but there was too much stuff piled up in front of the windows for her to see.

Jake picked up another coin and cocked his arm again. He turned to Dale and said, “He asked if my wife was that Jehovah blonde.”

He released the coin. It hit the window with another zing. Dale looked at her feet, fingering the end of her braid. A truck drove by and honked. Maybe a logger buddy of Jake’s, heading south to the next town.

A boxy blue car pulled up next to them. A woman with a flowered scarf tied around her long brown hair talked to a boy in the passenger seat. Rocks, leaves and feathers decorated the car’s dash, and beads hung from the rearview mirror. The woman climbed out. She wore sandals with no socks, but she didn’t seem to notice the slush as she walked into the store after looking at Jake and Dale and the can. The boy turned to look at Justy and nodded like adult men nod to each other. She looked away, pretending she didn’t see him or his blue eyes or his long brown hair in a braid down his back.

Jake pulled out a third penny, weighed it, cocked his arm and let it fly. When Dale took a step closer, Jake spun at her and grabbed her arms.

“He said he’d rather take food stamps than pennies from me,” Jake yelled. Justy sat back against the seat, fear pulling her shoulders in like a fallen bird. Dale took quick, short breaths and looked up to the Kingdom Hall. Snow continued to fall on their heads, and Jake’s spiky hair seemed to spear the flakes.

Jake released her and said, “I’m going to beat the hell out of him.” Dale didn’t turn as he started walking, but as he reached the door, she took a deep breath and said, “Maybe you could hunt.”

Jake stopped and looked at the back of her head. “What?” He cocked his head as if his ears needed cleaning.

“Whoa,” Lacee said. Micah looked at her and then nodded.

Dale turned to Jake, standing a little taller. “Maybe you could hunt.” She seemed surprised by her mouth, how easy those words ran from it. Jake placed a hand on the door, removed it, looked at the boy in the car and took two steps closer to Dale.

“You told me you’d leave.”

She cast a glance at the Kingdom Hall and said, “I’ve changed my mind.”

Jake looked at his hands, fists that knew how to find the solid soft parts of the stomach, the crook of the nose that would break. He clenched and then released his fingers. “And you won’t call the company like you said?”

She shook her head. Her lips formed the word no.

“You serious?”

Dale nodded. Silence filled the afternoon and Jake stood looking at his curled hands. The woman from the leafy blue car came out from the store. She stopped and took a long look at Dale; then her green eyes ran over the children in the truck and over Jake, and finally back to Dale. She opened her mouth but shook her head. She tried to meet Dale’s eyes, but Dale looked only at Jake, who gave the woman a curt nod before she climbed into her car. Her bracelets jingled and her deep blue dress flowed around her pale limbs as she moved. She and the boy watched Dale pick up the can and walk to the passenger door of the truck.

“Make room,” Dale said to Justy, who stood and pressed herself to the dash. Dale then pulled Justy onto her lap, placing the can back between their legs. Jake stood looking at his hands, and Dale’s heart surged in her chest. Justy looked at the blue car and saw the kerchiefed woman’s mouth shaped in a tiny oval.

“Don’t look at them,” Dale said. Justy sat up straighter, noticing that Micah was now in Lacee’s lap and that the two of them were almost on top of her and Dale. Jake climbed in and started the engine without a word. As they pulled away from the parking lot, Justy turned to meet the boy’s eyes once more.

***

“I don’t know what you want from me,” Jake said to the dark of the hunters cabin. His stomach lurched, and he decided to go to the orchard pasture by the old homestead. Maybe a deer or two would be out looking for a fallen apple. He walked to the cabin door and then stopped, the fiddle’s weight solid in his right hand. He moved back to the table and set the instrument and the bow down in the darkness. His fingers slid the smooth surface of the fiddle’s body as he remembered the night Kyle had given it to him, Jake’s eighth birthday. He and Kyle had lived in the house out at the Reese Ranch. There was a bottle of rotgut on the table that night. Kyle handed him a shot of whiskey, told him he was growing up now and produced the fiddle case from under his bed in the living room. Jake took a sip, shook his head against the hot sting and smiled. The family fiddle, one of the three things that had made it on the trip west. He reached for it, and Kyle held it from him for a minute before handing it over, a sloppy grin on his face.

“It’s time,” Kyle said and took a straight shot from the jug. “Daddy would’ve wanted you to have it.” Kyle wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and said, “And you’re old enough.”

He took another drink and seemed to slip away. Jake wanted him to come back, to show him how to play, but he knew not to bother Kyle when he was remembering. So Jake plucked at the strings until his father returned to show him how to tune the instrument, how to bend the bow when he tightened or loosened the strings. It had been a good night, Kyle playing and teaching and not too far gone.

Jake picked the A string, heard the cold air bending the note and walked to the door. He thought maybe now that he’d left the fiddle, he’d find a deer. Hoping, he moved through the night back to the truck.

***

The orchard was empty, the trees looking like skeletons in the overgrown rows. Each tree trunk was pockmarked by woodpeckers. The snow was too deep to see what he knew was there, the decaying apples and pears—fruit that Dale had wanted to can but hadn’t had the equipment. He’d promised her that next summer, he’d find a way. He wouldn’t have her borrowing the stuff from that scrawny JW woman, Joella. He walked from tree to tree, looking for deer signs. Two sets of faint tracks paralleled the fallen wooden fence, but it looked like they were passing through, not nosing the snow for fruit like he’d hoped.

As always when he came here, he thought about the family who had tried to homestead seventy years before. Maurer, that’s all he knew, their last name—that they’d moved away after fifteen years, after planting these trees and building a house that was only an ash pile and a few rusted cans now. Jake shined the flashlight up; snowflakes glowed as they passed through the beam. He wanted to know what had happened to their dream, where they went from here.

So stupid, he thought, to leave the fiddle—as though the world worked that way. He walked back to the truck and drove recklessly home, his earlier cautions about scaring deer, about spinning off a cliff, gone. The truck whined up and down the hills, and Jake turned his situation again and again in his mind. There seemed no way out until the spring and the work came. The other rifle from Kyle was in the pawnshop. Jake needed to get it back in the next two weeks before the owner sold it. He thought about pawning his chain saw but knew that didn’t make sense, especially if a firewood job came up. He could put the fiddle in with the gun, but the thought caused a sharp pain in his belly. He remembered the animals he used to trap with Kyle, the raccoons, the coyotes, sometimes even skunks. The traps Kyle used were metal and

snapped shut on a leg when the animal reached for the bait. As he drove, Jake wished for the sudden snap.

Less than a mile to the house, something pulled him from his thoughts. He slowed and the headlights revealed her, twenty yards ahead, standing in the middle of the road. The doe watched him, one foreleg poised for action, tail flashing its warning white. Jake left the engine running and climbed out, rifle in hand. Her eyes glowed brown and the petals of her ears stood erect. He leaned across the hood, bracing his elbows on the cold metal. He brought the rifle to his shoulder, right index finger on the trigger, left hand on the barrel rest.

Waiting, she watched him. He lined up the sights, switched the safety off and breathed, like Kyle had taught him. She lowered the leg and her ears flicked once. He pushed his glasses back and sighted again, looking away from her face. When he pulled the trigger, the silent night exploded with the sound and the deep orange flash of the shot. She crumpled where she stood, her front legs folding underneath her as if she were kneeling.

Jake walked to her, sliding the second bullet into the chamber in case she wasn’t dead. But he knew he’d shot her between the eyes. Blood ran from the wound, staining the snow around her ears. His head rang from the bullet, but he could still hear the snow adjusting to her weight. He knelt and placed a hand on her neck. The hide was scratchy and warm under his palm. He followed the arc of her neck to the body, and his fingers felt a little less on fire.

***

Justy woke suddenly and watched Dale worry her wedding ring. Dale stood when she heard the sound of the truck, and Justy remembered dreaming the river. The headlights curved out of sight as the truck neared the house. Dale paced the room, hoping against herself and her promises that he’d gotten a deer. Her shadow leaped in the candlelight. Justy wanted to tell her not to worry, but she caught herself and placed a hand over her mouth. Her tongue licked the edge of the penny she still held in her teeth. Dale sat back down on the couch and picked up her Bible.

Jake walked into the house, blood on his hands, his knife and his jeans. Dale calmly set the book aside and stood. Jake walked to the kitchen and washed his hands, dried blood flaking off in the water. Dale worked her palms together, fingertip to fingertip, her mouth hovering above the steeple of her hands. Justy watched her face, wanting to know how to compose her own.

He walked back into the living room, his candle shadow roaming the walls.

“What’s she doing up?” He pointed the knife at Justy.

“She couldn’t sleep.”

“Then she can help.”

Dale shook her head. “No. She shouldn’t see.”

Jake walked to the door. With his free hand on the knob, he said, “Bundle up. It’s cold.” He went out.

Dale worked her slight body into the windbreaker and brought in wood for the fire. Then she wrapped herself in a denim jacket and went into their bedroom. She came back with a quilt she laid on top of Justy, kissing her on the forehead before heading out into the night with a deer bag—two old sheets she’d sewn together last fall that they’d wrap around the body after it was skinned.

Wood shifted in the stove and Justy stood. She picked up the nearest candle and walked to the bedroom. Neither Micah nor Lacee stirred as she searched for Lacee’s cowboy boots. Someday the boots would be all Justy’s, but for now she usually wore them only when Lacee gave her permission. Justy returned to the living room, placed the candle on the floor and slid the too-big boots on her socked feet. She walked to the door, grabbed Jake’s logging jacket and stepped into the night, the boots clicking on the wooden porch. As she moved slowly in the dark, she smelled the old sawdust, gasoline and earth worn into the pores of Jake’s jacket, what she thought of as his summer smell. At the edge of the porch, she stopped.

Before her, caught in the headlights of the truck, Jake and Dale worked on the body of the doe hanging upside down between them. The deer’s hind legs were suspended by short lengths of rope from the lowest branch of the ancient Douglas fir just outside the fenced yard. Justy stepped down into the snow, placing the boots in Dale’s footprints. Neither Jake nor Dale heard her approach, and she stood back, watching them work.

Jake cut the skin away with quick, deft movements. He wielded the knife with precision, pulling on the hide after a series of horizontal cuts. Dale pointed the flashlight at the point of contact between knife and hide. They moved their way downward, each yank of skin separating from the body with soft tearing sounds. They worked without speaking.

Snowflakes landed on Justy’s hair, melting their way to her scalp. She remembered the look of amazement on Dale’s face in the parking lot and felt the waves of relief and regret washing through Dale now. The deer’s eyes were clouding over into a smoky green, like the river in springtime. Behind the smokiness, the doe’s eyes watched them from a farther and farther distance. She’s swimming away, Justy thought. It made her think about the photos Jake kept tacked on the barn wall. He had ten of them, stories that marked the years of his life. In one, he and the grandfather Justy didn’t know squatted, both holding rifles in their left hands. With their right hands, they each supported the head of a buck, holding on to the many-pointed antlers. In the photos, the men smiled similar smiles, but Jake was the darker of the two, his mother’s blood tinting his skin the slightest bit.

“Over here,” Jake said and pointed with the knife. Dale stepped closer and brushed into the deer’s ears. Justy shifted her weight quietly and did a quick tally of the pictures both Jake and Dale guarded. Dale kept her five photographs in a white envelope in the towel drawer, under empty paper bags with the towels on top. Dale looked at them only in the morning, after Jake had left for the woods in the dark of early day. Justy had seen her from the hall, sliding her fingers over the past. Justy knew both sets of pictures, knew Jake refused to look at the one wedding picture because Dale’s adoptive mother had hidden it when a neighbor remarked that Jake looked like an Indian.

These people confused Justy—this man and woman before her in the night. She wanted to know why they each kept a photograph from the year before her birth, when Kyle had still lived in town, when Jake and Kyle still played music and Dale sang—”like a bird,” Lacee said.

Lacee also said that it was during the pregnancy with Justy that Dale had stopped singing, when she promised two things to Jehovah. And here Jake and Dale were, standing in the middle of one of the broken promises, hovering on the edges of legal life once again. A poached deer didn’t seem that bad to Justy, not when she was this hungry. For her own sake, Justy wanted Dale to break the other promise, too, just once, so she could hear Dale and Jake in harmony. She shivered inside Jake’s jacket.

The deer’s hide was almost off and its head kept disappearing behind its own skin. Justy wanted to see its eyes once more, but she stayed put, wiggling her toes to keep warm.

Jake grunted and Dale moved again to shine the light where he wanted. Blood dripped from the cut jugular vein onto the snow at their feet. Crisp air and the odor of warm flesh swirled around them; they were almost done. Justy watched Jake’s hands, saw the strength in them when he yanked on the hide, watched his face to see how this day and night were settling on him.

Each time he pulled at the skin, he thought of Sullivan and his smug smile. Dale was worried about the double offense—how it was not just a poached deer but also female. She tried to keep her thoughts from the mining company, how they’d written a formal letter about any poaching on the land, making eviction entirely clear. Dale returned to her favorite passages from the Psalms, sliding away from the reality of her own bloodied hands.

When the deer was relieved of its skin, they both stepped back. So did Justy.

“You’ll want the liver,” Dale said without looking at him.

“Yes.” He wiped the blade on his right thigh. “It’s in the bed of the truck.”

She turned and started to walk away.

“Dale,” h

e said. She stopped, and Justy backed up some more.

“We ain’t got shit in this world.”

Dale paused, then said, “We are being tested, Jacob. And I failed today.”

Her words hit him and he stared. “What are you talking about?”

Justy retreated farther, feeling the rage build in him, run into his fingers.

“God offered us a test and I failed,” Dale said.

Jake threw the knife on the ground. “Dammit, Dale. There ain’t nothing wrong with a man feeding his family. I thought you finally saw the light on this.”

“I didn’t see that it was a test then, and I’ve been praying while you’ve been gone, and I see now. There are other options.”

“Bullshit there are other options. Don’t you think I’ve thought about this?” His words came from a lower and lower place in his throat. Justy moved back again, biting the coin, hating herself for not being able to step forward.

“There’s government help,” Dale said, taking a small step away.

“You know how I feel.”

And Dale did know, knew he’d never accept any help, not when his body still worked and there was the land to tell him who he was.

“In the old days,” he said, “it didn’t matter.”

“Tested” she said, “like Job.”

“We used to take what we needed. We didn’t need anybody telling us how to live, how to fill out paperwork.”

Dale closed her eyes.

“I am not in the Bible.” His hand shot out and punched the deer. It swung in a wild arc, the branch creaking under the weight. “Dale, I’ve done this all my life, and I stopped for you after Kyle left, but now we don’t have time to think about God.”

“Jacob. It’s wrong, even if I was the one to suggest it.” She started to walk away, but he caught up with her, grabbing her shoulder and spinning her around.

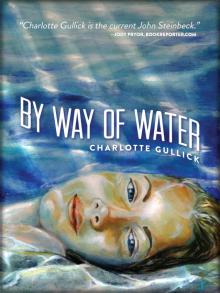

By Way of Water

By Way of Water